This is a long form analysis on Studio Ghibli's Arrietty, focusing on the psychological long-standing debate on whether nature or nurture plays a more important part in a child's development. If you are looking for a review on this wonderful and relaxing film, then you may be disappointed! But perhaps you'll find something here that gives you a different insight into a film that, on the surface, presents as a cosy, feel-good movie.

Disclosure: I am not a psychologist, nor a qualified expert on child development, thus I ask you take this analysis as the fun little project that I set it out to be! In this discussion, I theorise that a child's 'nature' is defined as their most natural state, a version of themselves that they genetically default to. With that being said, feel free to sit back, relax, grab a drink, and enjoy this analysis!

There are some of those spoiler-things below!

On Relationship with Nature: Arrietty and the Nature versus Nurture Mentality

Studio Ghibli’s 2012 film Arrietty is based on the 1952 novel The Borrowers written by Mary Norton. The whimsical Arrietty is another Ghibli masterpiece that allows the viewer to watch without needing to think too much. However, upon a closer analysis of the film, the relationships presented in the animation are a commentary on the discourse that occurs between family, as well as between humans and nature. These present as two different ideas, but due to how nature plays a part in how an individual grows up, conforming to the nature versus nurture mentality, you cannot talk about family without talking about nature. Moreover, Ghibli films often showcase nature in a such a way as to show how humans abuse the natural world, which in turn can create unhealthy relationships with each other.1

Arrietty and Childlike Wonder

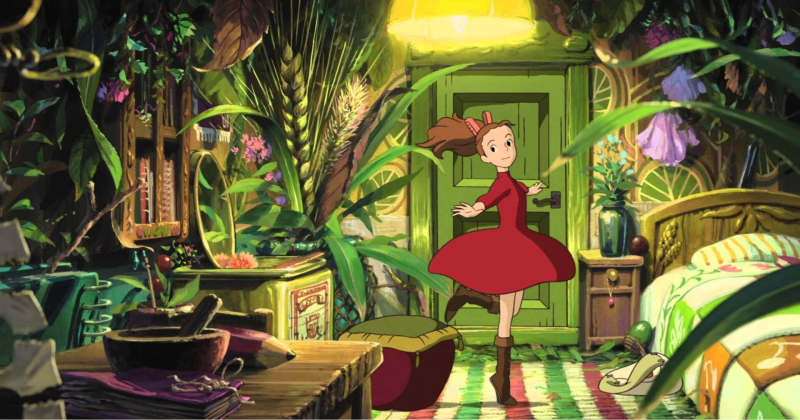

Arrietty Clock is the only daughter to Pod and Homily Clock. At the beginning of the film, she is excitable and bright-eyed – a young girl who has yet to experience the hardships of life. The Clock family are Borrowers, minute people who live in secret in the world of humans. Initially, the relationships between the Clocks seem healthy and respectful. Arrietty is cared for very deeply by her parents and is given space to explore a life of a Borrower when she is allowed to go out on her first ‘Borrowing’. Notably, she wears a brown dress for scenes where she is a curious and excitable child. Brown is the colour of neutrality, conforming to no stereotype and often seen as ambiguous and natural.2 In times where she must be responsible, she wears a red dress, often seen as the colour indicative of a woman coming of age. We shall discuss the importance of these colours in further detail later in the discussion.

Arrietty’s world, the hidden corners of the natural and human world, evokes childlike wonder and whimsy. It is beautiful and exciting, and encourages the viewer to imagine themselves in such a place. The human world is daunting, dark, and dangerous. It is the world we are the most familiar with, yet it doesn’t feel like a place we could get lost in. The natural world, the one full of animals and blooming flowers, is the middle ground between the human and Borrower world. It is a place without laws, a place that is neither safe nor unsafe, and full of opportunity. It is the neutral brown of the world, a place that Arrietty can be her curious and excitable self without those daunting pressures that come from the human world.

A Good Father

Pod Clock, Arrietty’s father, is a supportive parent. He balances caring for his child and allows her to be independent, thus recognizing both the inherent caring responsibilities and the natural progression of a child’s growth. When Arrietty accompanies Pod out for her first Borrowing, we see the man through Arrietty’s lens. He respects her, allows her to make her own decisions and mistakes, and gently shows her how to Borrow safely. Arrietty’s first Borrowing begins with Arrietty walking up some stairs behind her father. No words are uttered, and we only hear the rattling of equipment in Pod’s bag and the movement of it on his back. Watching this through Arrietty’s lens allows us to understand the responsibility Arrietty feels, as well as her childlike excitement of the new situation. Imagine your child self in a huge, unexplored expanse, following an experienced and impressive guide through the land. This scene evokes that childlike wonder of journeying through a land ripe for exploration, as well as the responsibilities that come with learning how to respect and deal with the land.

Pod expects Arrietty to do all the things he does without much fuss nor much direction, showing his respect for her and desire for her to learn at her own pace. When the Borrowing trips goes wrong after Arrietty is detected by a human, she, and her father leave, with Arrietty leading the way. She is ashamed of her failure, believing she has put her family at risk. However, her father doesn’t feel the same. In fact, Pod deceives Homily, Arrietty’s mother, when they return home without any items by saying that his light source wasn’t working, thus protecting his daughter’s feelings. Pod essentially allows Arrietty to explore her own nature, whilst gently nurturing her whenever she falters. He is a good example of a parent who understands that it is a positive and natural part of life for a child to make mistakes.3 Moreover, for Arrietty to lead the way home even when she is distressed, and does so safely, shows how mature she is becoming. On the way out to the Borrowing, she is led, but on the way home she is the leader. The Arrietty who returns home is not the same girl who left.

The Nature of Children

Despite the Borrowing experience making Arrietty more mature, she returns to a state of childish neutrality. Whilst the Borrowing trip had her wearing red, indicating her move away from being a child, she again wears a neutral brown dress once home. We see Arrietty sat alone, lamenting the failed trip. It is raining, and she watches the rain droplets pour as she thinks about her failure. No words are spoken, and we are reminded how small, literally, and figuratively, she is in the face of the world outside her family home. Adulthood is dauntingly vast for someone coming of age. Arrietty’s thought process is interrupted by a pill bug who crawls over her hand. She picks it up, and plays catch with it, making it curl up in defence. When she relinquishes the pill bug, it scuttles away, greeting another pill bug by rubbing antennas. This small interaction with nature shows how important the nature versus nurture mentality is for children. Arrietty’s shame comes from her family teaching her about the danger of humans, especially from her mother. She has been nurtured to be entirely dedicated, although genuinely loving, towards her family, and believes every lesson they teach her. Yet in this moment of vulnerability, Arrietty plays as a child would with a tiny, almost insignificant aspect of nature. Although I do not condone playing catch with pill bugs, her play with it shows how important it is for a child’s nature to be free, allowing them to learn about themselves in their own space, away from the influential moulding of their parents. Thus, her neutral brown dress represents the natural freedom of children.

A Questionable Mother

Arrietty’s mother, Homily, is emotionally abusive towards Arrietty. She is a very anxious person, perfectly acceptable given she is a Borrower living underneath a human house, a place full of people who could harm her. However, she does not comfort her only child after she returned from her unsuccessful first Borrowing. Despite Arrietty clearly looking distraught, Homily only focuses on the lack of items borrowed. When it is later revealed that Arrietty was seen by a human, Homily panics and laments the fact that they will have to move away from the house she loves. When the move becomes a reality, Homily does not reveal the truth to her daughter, instead remaining silent and essentially guilt tripping Arrietty. Homily emotionally punishes Arrietty by not being the mother figure she needs in times of distress, which in turn pushes the young girl to take on an adult role that far exceeds her age. Amusingly, Homily possesses a mentality that “children can be more terrifying than grownups”. Children have less awareness and experience in many situations, usually approaching life with excitement and curiosity which can lead them to making poor choices. They are innocent and malleable, learning how to act from the world around them.4 For Homily to believe children can be this way, and to be as anxious as she is, suggests that she herself did not have a positive growing up experience that shaped her mentality of children. In turn, her fear of children and humans was passed on to her own daughter. Her anxious nurture-style shapes her child to be less curious about her world, essentially preventing Arrietty’s own nature as an inquisitive child from flourishing as much as it could.

The Colours of Adulthood

Arrietty dons a red dress and ties her hair up with a small red peg in times where she must act the adult. She wears one for her first Borrowing, which is essentially a ‘coming of age’ event for a Borrower. She also wears one when she must venture back out into the human world to save her family and stop the humans from further damaging her family home after its existence is revealed. The colour red has long been stereotyped to be a symbol of femininity and coming of age when donned by a woman. Indeed, Arrietty wearing red is a symbol of her coming of age. However, Arrietty’s red frock is used to empower the character, to give her the confidence she needs to achieve great feats. She only wears the red dress when she is determined, otherwise wearing a neutral brown dress. When she wears brown, she is less confident in herself and more childlike, often seen to be losing herself to the guilt of letting her family down, evidenced with her playing with the pill bug. The expectation that she must serve her family and the lack of freedom to form her own opinion about humans, depicts her loss of freedom and childhood. When she dons the red dress, she essentially dons the right to be free. In fact, she is more focused and less excitable in red than when she wears brown.

Despite her determination to save her family by righting her wrong when she revealed herself to a human during her first Borrowing, Pod warns her that she is still putting the family at risk. Although Pod is correct in his thinking that the Borrowers are in danger from humans simply because they are small and humans are big, he is nurturing his daughter to believe that she isn’t being responsible. This only reinforces Arrietty’s desire to be an adult, spurning her to keep returning to the human world to convince the humans to leave her and her family alone. By nature, Arrietty is a ‘brown’, curious child. By nurture, she is a child wearing the ‘red’ persona of an adult.

Essentially, the colour red is the colour of adulthood and responsibility for Arrietty. But because of the pressure that comes from her parents, again, notably her anxious mother, she is being nurtured in a way that promotes her choosing adulthood over being a child. In fact, Arrietty chooses to wear red more and more throughout the film, suggesting that although she is only fourteen, she is no longer able to be the child that comes with the neutral brown colours she previously wore. It is fascinating to consider how children are the ‘neutral zone’ of being human – they are innocent and curious, without the pressures, the ‘red haze’, of adulthood.

Arrietty and Shō

Arrietty’s self-confidence contrasts that of Shō’s. Shō is a young human boy who is the first character we see in the film. He is important to the film because he is the human lens that we can most relate to, given we are human, not Borrowers. He is the only son of a mother and father who work all the time and are getting divorced. He has been sent away to live with his aunt for a week during the summer to recuperate before a life-changing surgery on his ailing heart. He has no one his own age to interact with, not that he is allowed to, given his heart is too weak to keep up with other children. We see him reading and sitting alone much of the film, clearly a very lonely child. He masks as being okay when he is not, showing he tries to put the wellbeing of others above his own by ensuring they do not worry about him. This is a lot for a young child to deal with alone, which shapes him into a realistic and occasionally thoughtless person. This is shown when he gives the Borrowers new furniture, gifted to them by ripping the roof off their house. In his eyes, he was being kind, but to them he was dangerous and disruptive, and ultimately spurns the family to leave their home.

Shō cannot be the child he is, much like Arrietty, but his adult-self is far less confident than Arrietty’s. Due to his poor physical health, he has been ostracized his entire life, especially by his own parents. He has been shaped to believe himself to be fragile and incapable of doing activities that other young children his age engage with. Of interest, Shō got the new furniture for the Borrowers from a dollhouse that his mother previously owned, with it being built to house the small people that she herself once saw. Now, years later, Shō wishes to use the dollhouse to interact with the Borrowers, just like his mother. However, the adult version of Shō’s mother has most likely long since forgot the Borrowers, choosing to work away from her sick son. This reinforces the idea that childlike wonder is lost when someone enters the adult world.

Children as Adults

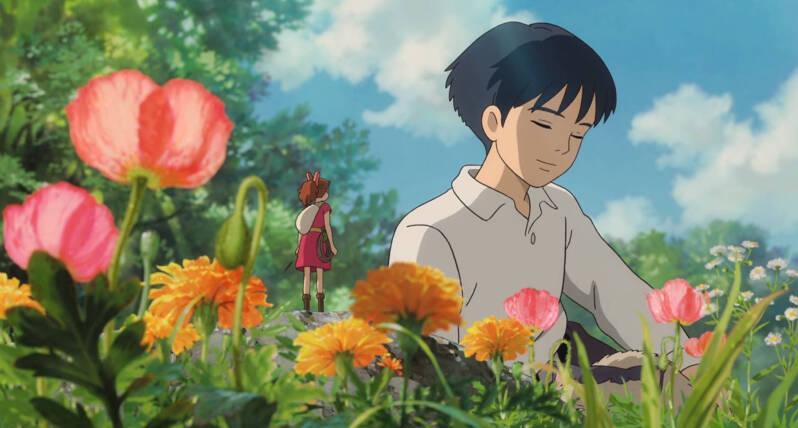

Arrietty and Shō simultaneously clash and get along because they are both children and full of curiosity yet are also expected to act far more mature than their age. One point of contention between the pair is due to some of the topics Shō talks about, ones that reveal how he has been brought up to be serious and realistic. Later in the film, Arrietty and Shō finally meet face-to-face. Shō sees Arrietty as beautiful, but more so because a Borrower is an exciting reality to him. He calls the Borrowers a potentially doomed species, essentially treating her like a specimen or animal to study. He does this because he too has been treated as a doomed species, a creature to be cut open and studied. He accepts and reflects the mistreatment from his family who view him as weak and unable to be a normal boy. For him to gift the Borrowers with new furniture but then call them a doomed species shows the nature versus nurture mentality as work. By nature, Shō is a kind and gentle boy who loves nature and everything and everyone in it. This is evidenced in the film when he chooses to lay outside in a field of flowers, stroking the family cat. By nurture, however, Shō is cold and uses his intellect to make himself seem more impressive. His suggestion that fate might have death in store for the Borrowers, simply because he observed that there were only three of them living in such a large space, is a result of being nurtured to believe that the weak die.

Of course, Shō’s fate-talking angers Arrietty. He believes the fate of the Borrowers are a result of their environment being destroyed and harmed. Arrietty, however, states "Fate you say? You're the ones who changed things as we're the ones who must move away."5 Here we see that the Borrowers are indeed a species separate from humans, shown through the 'us and them' mentality, or at least that is what Arrietty has been made to believe. Factually, the Borrowers are endangered by the harmful meddling of humans, who cannot leave things alone to thrive in their own natural state. Conversely, if Arrietty wasn’t taught to fear humans and to stay a secret from them, perhaps the family would not have garnered so much fascination from the humans, instead being a normal aspect of life, thus removing the 'us and them' mentality. Shō apologies for upsetting Arrietty, revealing that he wanted to protect her and her family because that is the only thing he can control. After all, Shō is not allowed to be a normal child because of his heart. He lost his freedom to be a child because of the way he was nurtured. This is very similar to how Arrietty was nurtured. Arrietty and Shō bond over the loss of their freedom.

When the film reveals that there are other Borrowers living close by to the Clock family, the isolation the Clock family experiences changes. Spiller, a ‘rough and tumble’ teenager, is introduced when he saves Pod when the man left to search for a new home and got injured. He is less civilised than the Clock family, who, unlike Spiller, have had the luxury of Borrowing directly from humans. He is an example of what happens when a child is exposed to all nature and no nurture, given he does not have a family. Without the guidance of a family, he had to learn how to survive in nature, reverting to a less civilised state where his communication and dress sense differs to that of someone who has lived in a society. However, he is of great interest to Arrietty. She believes that Spiller’s existence, “[the knowledge another Borrower exists,] makes [her] feel better.” This reveals that Arrietty, much like Shō, has been lonely in her short and young life. The three children of the film are all different, with interests that make them stand apart from each other. But one unifying theme ties them all together: children are shaped by their environment.

Humans versus Nature

We were all children once. We started life curious and without the pressures of adulthood. Studio Ghibli films are well known for their commentary on the negative effects humans have on nature, and Arrietty is no different. The humans in the world of Arrietty, Shō included, are all shown to be mostly destructive and unfair to the natural world around them. The adults are often shown to be uncaring or disinterested in the natural world, notably with the character of Haru. Haru is the maid working at Shō’s aunts house and is the main antagonist for the film. She is determined to bring the existence of the Borrowers to light, going as far as to call exterminators in to capture them. When Shō gifts the Borrowers new furniture, it is Haru who discovers that the young boy knows of the Borrowers and is led to where the Clock family lives. Her lack of respect for the Borrowers, and her determination to destroy their little slice of life, shows her to be a human who has disregarded nature, given Borrowers are in essence part of nature, essentially on the same level as fairies or nature spirits. Haru’s antagonistic actions towards the Borrowers results in her kidnapping Homily, placing her in a jar covered with cling film, piercing holes in the cling film to give the Borrower air, and then stowing her away in a food cupboard.

This scene is reminiscent to Shō’s comment that the Borrowers are a doomed species, and his opinion that they are animals to study. Like a child who stores insects in a jar to study them over time, Haru places Homily in a place that she can visit and study her, representing a perturbing museum-spectator mentality.6 However, Shō teams up with Arrietty to save Homily, choosing his kind nature over the cold nurture he was taught. With the pair bonded over their shared loneliness and determination, they work together to free Homily. Despite his heart problems, Shō dashes around with Arrietty on his shoulder, deceiving Haru, and acting the sick child to get the maid to follow his requests. There is a beautifully poignant moment where Shō pretends to conform to the fragile boy mentality that he has been subjected to his entire life to save Homily, showing he has gain some confidence in himself. The interactions he has had with Arrietty, who in these scenes is wearing her determined red dress, has in turn made him more determined. The pair save Homily, meaning the family can reunite and, with heavy hearts, leave their family home to find somewhere where humans cannot find them again.

The Natural Conclusion

In the final scene of the film, Arrietty and Shō reunite once more to say their farewells. They love each other, having bonded over their shared desire to remain children, despite their responsibilities and the somewhat subservient relationships they have with their families. The scene in which they say their farewells is set in an incredibly interesting scene. Behind Arrietty, in her confident and adult red dress, is a city scape, the land of humans. The city is coloured in dark tones and is absent of the splendour of nature. Behind Shō is nature: tall, luscious trees and flowers. In a turn of events, it is Arrietty who is moving towards a life that matches our reality of the human world, one where nature isn’t always cared for. Meanwhile, Shō, who came from the city-oriented human world, has moved towards nature. His friendship with Arrietty taught him to respect that natural world, opening a whole new world for him to care for and explore. It is a tragic scene to end such a beautiful film on, given the backgrounds suggest that Arrietty has grown up to the point where she is leaving the childlike wonder of childhood behind in favour for adulthood. But, Shō, the boy who was seemingly doomed to be alone, is given a chance to see life differently. Perhaps, then, it is Shō who is the Borrower, essentially borrowing Arrietty’s determination for his own future.

Footnotes

- Huerta, S.M. 2021.

- Allen, K. 2011, pp. 153-326.

- Epstein, A. 2010, pp. 46-51.

- Gittins, D. 1998, pp. 145-146.

- Arrietty, Studio Ghibli.

- Baker, 2010.

References

Allen, K. 2011. Revelation and the Nature of Colour. Dialectica, Volume 65, Issue 2.

Baker, J. 2010. Affect and Desire: Museums and the Cinematic. Curtin University.

Epstein, R. 2010. What Makes a Good Parent? Scientific American Mind, Volume 21, No. 5.

Gittins, D. (1998). Are Children Innocent? In: Campling, J. (eds) The Child in Question. Palgrave, London.

Huertas, S.M. 2021. Humans, Nature and Spirits: An Ecocritical Analysis of Studio Ghibli’s Films. Skemman.

Create Your Own Website With Webador