This is a semiotic (relating to signs and symbols) analysis of Ponyo. If you’re looking for a review, then you may be disappointed. But with all things in life, variety is the spice of life - perhaps you will learn something new about one of my favourite Studio Ghibli films?

There are some of those spoiler-things below!

An interpretation of the depiction of nature in the Studio Ghibli film Ponyo

Ponyo’s themes are not as mysterious as others in Hayao Miyazaki’s Studio Ghibli films. In essence, Ponyo is a dreamy children’s film which excites the mermaid-loving viewer without forcing them to think too much. Or at least, that is one way to enjoy the film. Fundamentally, Ponyo is Miyazaki’s artistic commentary on the turbulent relationship between humans and nature, specifically the ocean.

Artists, writers, and game-designers frequently employ the concept of world-building to intertwine real-life challenges with elements of fantasy, enabling them to explore and provide insights into issues related to ecological responsibility, sustainability, peace, and social justice.1 Miyazaki is a master world-builder. With Ponyo, his oceanic world being both beautiful and at the mercy of humans offers us an insight into human’s relationship with the environment, our imagination of it, and how we can improve it.

The Bucket Prison

Sosuke, the young son of eccentric mother Lisa and always absent sailor Koichi, finds a unique ‘goldfish’ (Ponyo), trapped in a glass bottle. As a child with little experience in taking care of animals, Sosuke roughly removes the fish, and puts it in his green plastic bucket. The bucket symbolises a prison, one that only humans can manufacture. For a human to trap a creature of the ocean in a plastic manmade object, the human is essentially imprisoning the creature in the destructive trappings of human nature. The creature loses the freedom and beauty the ocean offers and is faced with the less free human world. When Fujimoto, the fish’s over-protective father, observes Sosuke taking the fish, one of his daughters, he sends dark-coloured waves to forcefully take the fish from Sosuke, but fails to do so. Sosuke’s bucket prison stands firm against the ocean, reinforcing the fact that humans destroy the ocean with pollution, waste created by humankind.

The bucket alternatively symbolises a bridge between the ocean and humans. The bucket is seen repeatedly throughout the film, mostly in Ponyo’s hands. Given Ponyo’s affinity with the ocean, her holding the bucket represents her determination to keep hold of both her oceanic heritage and the human world. Releasing the bucket would be her admitting that she cannot experience both the magic of the ocean and the land. When Ponyo is taken back to the ocean by Fujimoto later in the film, Sosuke leaves the bucket in a place he hopes Ponyo would be able to see it. When a storm (notably created by Ponyo and discussed later in this analysis) wreaks havoc for the characters, Ponyo returns to Sosuke, holding the green bucket, which then gets blown away in the wind, into the ocean, ultimately adding to the human pollution. In this case, the bucket inspires Ponyo to break free from the confines of the ocean, as well as the bucket itself, embracing a life on the land. For arguments sake, her losing the bucket in the ocean also represents she can now develop the capacity to destroy the natural world, as someone who is choosing to walk the land as a human.

The bucket represents the discourse between the ocean and the human world in the beginning of the film, eventually becoming a symbol of hope and unification later in the film. Ponyo’s attachment to the bucket represents her desire to break the cycle of hatred between ocean and land, as well as her love for Sosuke, who gave her the bucket and thus a chance to live on the land.

The Unfathomable Deep

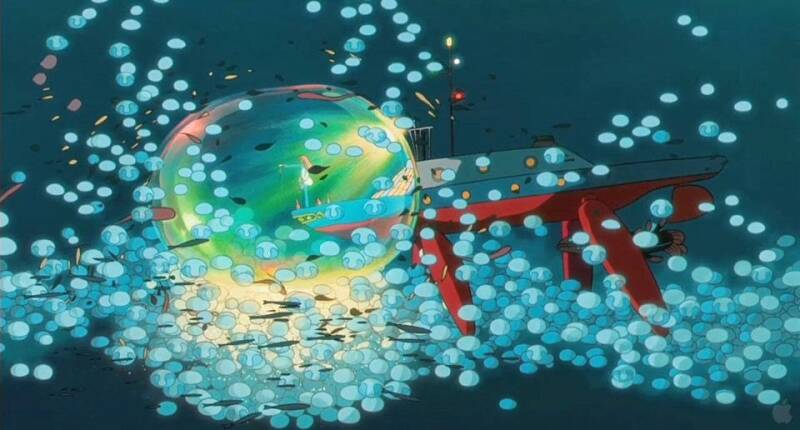

The ocean is the first scene we see in the film, with several ships gliding on the waves. The colour palette is wondrous but significantly muted compared to that which lies beneath the surface. The film focuses on what happens beneath the waves, revealing a beautiful oceanic serene, idyllic, and fantastical. We meet Fujimoto, an eccentric wizard-like human whose duty is to add potions to the ocean to keep it healthy and vibrant. The introduction to the film is meant to be playful, representing the whimsy of the sea. Despite the splendour that can be found here, Brünnhilde, Ponyo’s given name, wishes to leave, enchanted by the warmth of the sunshine, something that can only be enjoyed on or near the surface. As Ponyo finds rest on a jellyfish, preserved underneath a bubble of water, the film moves to a vibrant title sequence which make the ocean appear all-encompassing. The boats on the waves are but specks on the vast ocean, with the human’s houses perched precariously on islands. The breadth of the ocean, although bright and beautiful, belittles the surface world, making the houses seem irrelevant compared to the waves. The waves themselves are large, towering over everything manmade. Even grass, something natural, is made to seem irrelevant, with the waves threatening to consume them.

The use of colour in this title sequence highlights that both the surface and beneath the waves are beautiful in their own ways, but the surface lacks the magic of the ocean. Whilst Fujimoto’s submarine is a rainbow of colour, the surface is comprised of block colours, bland and simple. We are meant to feel disgusted at the human world, and enchanted by the ocean, perhaps even upset that the ocean’s beauty is being tarnished by the land. The specific use of colour is Miyazaki’s way of commenting on how we should care for the world we have, and love it back to life, not pollute it to death.

We first get to see the human world through Ponyo’s eyes, in which she gapes in amazement at the buildings and boats she has yet to see. When she first sees Sosuke on the land, playing in the surf, she is captivated, but is quickly brought back to reality when a boat approaches, using a large fishing net that captures fish and trash alike. It scoops up the harbour bed, scraping away at it like you would use a spatula to scrape off bacon scraps from a pan. The boat makes the waters muddy, ugly, and dangerous – a manmade object manned by humans is destroying the ocean. Ponyo gets stuck in a discarded glass bottle but is swiftly saved by Sosuke. However, the gauntlet of the fishing net has seemingly stunned the fish for she appears dead, if not stunned. Sosuke’s rescue of Ponyo is rough, with much pulling and tugging, yet is clearly an act of love for nature. Given his age he does not know how to remove the fish carefully, however he appears upset that the fish is in peril. Sosuke’s young age is important because his love for the fish, his desire to look after it, triumphs over his potential, as a human, in polluting the ocean. Whilst Sosuke is young, he has less an inclination of ruining the natural splendour of the ocean. This scene is a commentary on children being a way of saving our world, because they can be moulded much easier than adults to respect and love our world due to their innocence and inexperience of consumerism.

However, Sosuke’s actions in saving Ponyo angers the ocean. Dark-coloured, literally frowning waves are sent by Fujimoto, rushing towards the young boy, wanting to take back the fish that he has imprisoned in a green plastic bucket. Sosuke manages to escape the waves, leaving behind the glass bottle that Ponyo was stuck in. The emphasis on Sosuke leaving the trash behind is meant to give more reason for Fujimoto’s hatred for humans, despite him being one himself. If Sosuke truly cared for the natural world, he may have recycled the glass bottle, rather than focusing on the fish. Perhaps Fujimoto’s desire to isolate himself from other humans is because his love for preserving the ocean means he sees all other humans as destructive and unloving towards nature, and he doesn’t want to be associated with them. Nevertheless, Sosuke is only a child, so he is not to know better, thus his desire to save marine life is admirable.

Consumption of Flesh

In the first moments of Sosuke and Ponyo bonding, in which Sosuke gives Ponyo her name, Ponyo tastes Sosuke’s blood. Blood has significance in many pieces of literature and media. It can be the lifeforce that can feed sanguine-hungry creatures. It can be the fuel for powerful spells. It can also be the representation of innocence, with blood-shedding being part of a woman growing up. Blood can also be a symbol of war and danger, being shed immorally on the battlefield, or taken by a person wishing to do harm. The importance of Ponyo drinking Sosuke’s blood in the film lies with the Japanese belief that blood is powerful. In one myth, the Jubokko or yōkai tree sucks up the blood of the dead, usually on battlefields, using it for food.2 A yōkai tree supposedly captures its victim, a human being, as they pass by, and feeds on its blood, allowing it to maintain its fresh appearance. When Ponyo drinks Sosuke’s blood, it enables her to take on a human form. She also heals Sosuke’s wound.

Breaking down Ponyo’s consumption of blood, the discussion of her being like a yōkai tree, something that can only create a fresh appearance with human blood, takes away from the childish whimsy of the film. However, it is fascinating that the magic to make her into a human relies on human blood. Given Ponyo’s age and her desires to experience life on land, her use of human blood is one of innocence, something she does offhandedly whilst simultaneously healing Sosuke. But if she was older, or perhaps inherited her father’s ugly disposition on humans, she may have used Sosuke’s blood for evil. After all, Ponyo does create an almighty storm that threatens the entire land in the film by combining the ocean with an influx of her father’s magic potions, showing she could cause others extreme harm. Ponyo’s young age and inexperience shown with her reckless creation of the storm shows that she is at a stage of great change. She could get a very literal taste of blood and destruction and decide to pursue such discourse. Or, like Sosuke, because she is still young, Ponyo could be taught how to respect and love our world.

Consuming parts of human, flesh or specific organs and gaining their power or wisdom was a relatively common trope in many folklore and stories from long ago. It is difficult to think about the consumption of humans in a way that does not elicit immediate disgust. The word cannibalism itself is often used to describe someone who consumes others ravenously, barbarously, and with extreme debauched revelry. But there have been historical accounts of therapeutic cannibalism, used for medical treatment, usually regarding spiritual or occult practices.4 Pliny wrote that the drinking of blood itself was supposedly a cure for epilepsy.5 Thus, if we view Ponyo’s “medical vampirism” as her way of curing herself, perhaps then she is trying to cure herself of being an oceanic creature. Conversely, the ocean is meant to be a beacon of beauty and purity according to its enchanting depiction in the film, thus her blood drinking may in fact be her trying to heal the bond between the ocean and the land. If she consumes part of a human, thus making her human, or at least part human, she is establishing a direct, biological link between the ocean and humans.

The Colour of Nature

The use of colour in Miyazaki’s Ponyo, and in fact all the Studio Ghibli films, has always been a representation of creative and artistic beauty, works of a fantastic imagination. Miyazaki is a naturalist, and it shows in his creation of some of the most beautiful and appealing stories, scenes, landscapes, and characters that exist in the film industry. In Ponyo, colour is used to show that it is tragic how nature is often destroyed, tainted, or perverted by the destructive nature of humans. As we have already discussed, Ponyo’s beauty is tarnished by humans polluting the ocean, hence the colours of the ocean are much brighter and fantastical than the grungier land of the humans. Specifically, the ocean is painted with brighter, fantastical colours, whilst the land does not hold the same magic, the same fictional splendour, that the ocean has. For instance, the fish, coral reefs, Fujimoto’s submarine and outfit, and bubbles seen below the ocean’s surface are dreamy colours, pinks, blues, greens, and purples. These colours spark our imagination, transporting us into a realm we can never physically be in. The land are all colours we are familiar with, browns, greens, blue skies, and fluffy white clouds. Although the land is beautiful, and has the rolling hills, dense forests, and blooming flowers all associated with an idyllic landscape, it doesn’t hold the same magic as the ocean does because we are already familiar with the land, because we live on it. Essentially, colour has the power to shape how we feel and think.

The same power shapes how we think about Ponyo’s characters. Ponyo’s colour palette, specifically her pink outfit, is stereotypically associated with femininity. Because colour is a matter of perception, it is important for an artist to use them in a way that best represents their themes and appeals to their audience.3 Fundamentally, the colour pink is perceived as something that represents femininity, maternal love, sensitivity, and tenderness. Thus, Miyazaki’s use of pink for Ponyo is intended to create a sensitive and tender character who is perceived as a young, innocent girl. But what does the colour pink do in a film that is essentially a whimsical commentary on the discourse between the ocean and humans? By creating a character who is endearing, one who is sensitive, young, and female, the audience is more likely to be accepting of the themes that are associated with them. We have established that Ponyo is the bridge between the ocean and the land, someone who could mend the bonds tarnished by discourse. Thus, an audience who likes Ponyo, who wanted to see her flourish, is more susceptible to the idea of caring for the natural world. Miyazaki’s naturalism is something he wants his audience to emulate.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, we have Granmamare, a representation of powerful femininity whose appearance is a statement on how beauty can command others. Granmamare is the goddess of mercy and the Queen of the ocean, wife to Fujimoto, and the mother of Ponyo and all her sisters. Her vibrant red hair, glistening red jewellery, voluminous form, and pale blue frock all contribute to her being a powerful goddess who expects and demands respect, all while being enchantingly beautiful. Her pale blue dress represents her motherly and calm personality, someone you believe can and wants to take care of her family. She can also command the ocean to do her bidding in destroying ships or safeguarding them. Therefore, her red jewellery and matching glistening ruby red lips give her an all-powerful, almost domineering appearance. The colour red is often associated with blood, and can be used to represent violence, bloodshed, and danger. If Granmamare wanted to, she could destroy an entire ship, condemning its sailors to death. Essentially, her powerful colour palette and her calm, untroubled demeanour, contributes to the theme that the sea and humans can have a gentle familial relationship, as long as humans respect that the sea is unfathomable and dangerous. If we accept our role as protectors of the ocean, the ocean in turn will keep contributing to our well-being by providing us with food.

Conclusion

The balance between nature and man has been tumultuous in recent years. Pollution, global warming, and resources running low all contribute to our world declining. It is hard to stop and realise the beauty our world has, and sometimes even harder to know how to protect it. Ponyo goes a long way in showing its audience that we can create harmony between humans and the natural world, specifically the ocean. It’s fun and playful premise of two children befriending and loving each other appeals to a wide audience, broadening the chance that someone watching might just decide to take action in safeguarding nature.

Miyazaki’s films loudly broadcast the message that humans have the capacity to destroy everything they touch, and despite it’s fantastical and mermaid-loving surface appearance, Ponyo does the same. From the bucket prison that both represents the trappings of human nature and the possibility of harmony between the ocean and land, to the more sinister side of the ocean, the one that can give and take life, Ponyo serves to entertain and teach. You can watch the film, wrapped in a blanket, and lose yourself in a mermaids and friendship-themed fantasy, not needing to engage with the naturalist message. Or you can consider that the images, colours, and gestures depicted in Ponyo share a semiotic importance that reveals the film is a complex commentary on the discourse between the unfathomable deep and humans.

Footnotes

1 Gossin, 2015, pp. 209.

2 Foster, M. D., & Kijin, S. 2015. pp. 3–32.

3 Rhodes, M. 2020.

4 Rhodes, M. 2020.

5 Brownlee, P. 2009. pp. 21.

References

Brownlee, P. J. 2009. Color Theory and the Perception of Art. University of Chicago Press.

Foster, M. D., & Kijin, S. 2015. The Book of Yokai: Mysterious Creatures of Japanese. University of California Press.

Gossin, P. 2015. Animated Nature: Aesthetics, Ethics, and Empathy in Miyazaki Hayao’s Ecophilosophy. World Renewal, Vol. 10, University of Minnesota Press.

Hackett, J. & Harrington, S., 2018. Beasts of the Deep: Sea Creatures and Popular Culture. Indiana University Press.

Rhodes, M. 2020. A History of Medicinal Cannibalism: Therapeutic Consumption of Human Bodies, Blood, & Exrement in “Civilised” Societies. A History of Medicinal Cannibalism: Therapeutic Consumption of Human Bodies, Blood, & Excrement in “Civilized” Societies - DIG (digpodcast.org).

Create Your Own Website With Webador